The original version of this post was written five years ago. It’s tragic to note that, since then, not much has changed; in some ways the situation has become worse. On the Feast of the Holy Innocents, this is something we need to confront; on the brink of a new year, this is something we need to take forward.

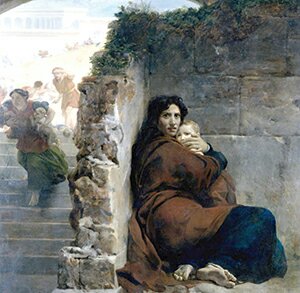

It’s the Christmas hangover of commemorations, isn’t it? The joy and beauty of the Nativity give way to the world’s brutal realities as Herod’s death squads march into town.

It’s not a part of the story we like to think about too much, a liminal atrocity on the fringes of the narrative. And yet so many of those kneeling beside the manger are either affected or complicit – Herod issues the order, sure, but it’s inadvertently thanks to the blunders of the Magi. Jesus, Mary and Joseph have to flee to Egypt, but what of the shepherds left out in the fields? Did any of them have infant sons waiting for them at home?

We pretend, of course, that this sort of thing is rare. That we live in a civilised society where children are valued and loved. And yet there are 4.2 million children living in poverty in the UK (that’s gone up since I wrote my original post); UNICEF reports that one in six children globally live in extreme poverty. The UN tells us that around 33 million of the world’s refugees are under 18, but it takes a photograph of one of their bodies washed up on a beach to make us give a damn about that statistic for five minutes. Churches cover up child abuse.

Herod casts a long shadow.

Over recent years, I’ve slowly begun to appreciate the wisdom of the church calendar. Not just the big celebrations, but the hidden feast days, the obscure remembrances, the idea that someone somewhere decided it would be good to honour Herod’s victims, and in doing so remember all the other infant victims of our politics and greed, our rage and corruption. Childermas isn’t just a call to memory, it’s a call to repentance.

And yet there’s also space for hope – there has to be, because this is too important to fall victim to nihilistic cynicism. There are people working to end child poverty, people operating shelters so families can escape domestic violence, people opening their homes to refugees. They need our support and our prayers, because they’re saving children from war and want, violence and apathy; because they’re a sanctuary along the flight to Egypt; because they’re building the Kingdom of God in the shadow of Herod’s legacy and that’s a sacred calling, at Christmas and beyond.

“A voice is heard in Ramah,

“A voice is heard in Ramah,