We heard it again this week, in a casual conversation. As so often happens, it wasn’t even solicited, a pre-emptive answer to a question we didn’t even ask, for goodness sake: “Oh, our church couldn’t cope with your children. We wouldn’t know how.”

It’s hard not to come away from stuff like that feeling angry and frustrated. It never gets any easier, seeing your children ‘Othered’ so casually. So many churches like to believe they love everyone equally; the truth is, we love some more equally than others.

The thing is, I don’t think this is rooted in prejudice or deliberate policy. I genuinely think this stuff happens because people are scared. Scared they don’t have the resources, scared they don’t know sign language, scared they won’t know what to do in the event of a meltdown, scared they don’t know how to talk to someone who communicates in grunts and shouts. And when people get scared, the barriers come slamming down.

But here’s the thing: fear’s only helpful if you’re being chased by a rabid grizzly and his mates and you need your fight-or-flight impulse to kick in before you’re eaten. Meanwhile, biblically speaking, “do not be afraid” could almost be God’s catchphrase – he shows up and it’s often the first thing he says:

In the face of danger? “Do not be afraid.”

In the face of a difficult future? “Do not be afraid.”

In the face of your enemies? “Do not be afraid.”

In the face of angels and miracles and the Holy? “Do not be afraid.”

When you’re sitting in a room with children with disabilities? “Do. Not. Be. Afraid.”

Look, I’ll be honest here: sometimes I find life terrifying. I’m scared of how we’d stay afloat if I got made redundant or couldn’t work. I’m scared of what would happen to the boys if/when something happens to me or my wife. I’m scared I’m not good enough at this whole parenting thing because I look around and other people seem to be so much better at it than me. I’m scared that statutory authorities are throwing disability services under the bus as part of their ongoing cuts. I’m scared of the phone call that announces the next bout of mickey-taking random lunacy. “Do not be afraid” is often easier said than done.

But that’s external stuff. My children? They’re not frightening. They’re intelligent, loving young people with individual personalities, quirks, likes and dislikes. They have additional needs, sure, but they’re far more than their disabilities. The Church Universal and Triumphant doesn’t need to be scared of them, because like everyone else they’re made in the image of God and he loves them, cares for them and wants to see them integrated into his family. All those times Jesus reached out to those considered to be on the fringes, out of the mainstream, the marginalised and the “scary”? He’s our role model. If he’s not, if the Holy Spirit isn’t working to constantly make us more like Jesus then our churches are just social clubs and they won’t change a damn thing.

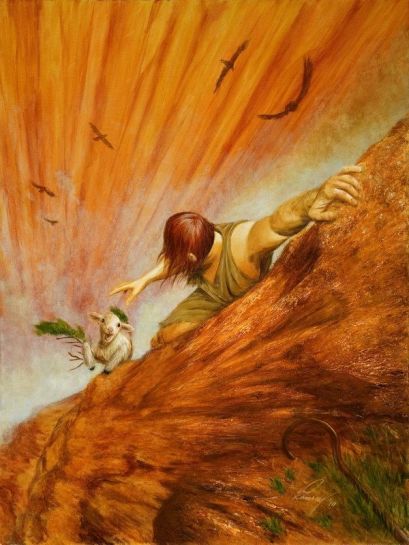

But beyond that, I need to trust that God has our backs, that he prepares a table for us in the presence of DLA forms and austerity cuts and societal ignorance. When we’re clinging to the cliff face by nothing but our fingernails, I need to trust that God will catch us. And I’ll be honest, I find that so hard because in this jenga-esque life it feels like we’re just one wrong move away from everything crashing down.

And yet we’re still here. We’re still standing, still laughing, still eating and paying the mortgage and looking after two wonderful children who are growing up safe and healthy. God has brought us through a hundred storms, and though I still get nervous every time I see a cloud, he’s there beside me whispering “Do not be afraid.” Even when the clouds are dark and the lightening flashes. Even when I’m not listening.

Maybe I should listen more, right?

Maybe we all should.

Do not be afraid.