They were walking to Emmaus, about 7 miles from Jerusalem. About 130 years earlier, this had been the site of a great battle, Jewish rebels triumphing over Greek forces. After Herod the Great died thirty years earlier, the village was burned to the ground after the inhabitants attacked a Roman garrison. Now it had been rebuilt and become home to a disciple called Cleopas, who was now trudging his way back from Jerusalem, the aftermath of the crucifixion bearing down on him.

We celebrate Easter Sunday as a glorious explosion of new life, but as he walks the road to Emmaus, Cleopas is still living in Saturday. He’s leaving Jerusalem, where within the space of a week Jesus has gone from being popular hero to an abandoned victim of conspiracy and crucifixion, all the hopes and expectations of the last three years nailed to a blood-soaked plank of wood. On the horizon is the site of a Jewish victory, yes, but that had been a long time ago and Herod had showed what happens to anyone hoping to change the world.

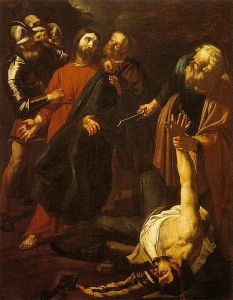

So when Cleopas encounters a stranger on the road, he explains the situation with a sense of loss: “We’d hoped he would be the one to redeem Israel.” With the benefit of hindsight we can smile at how Cleopas is missing the point – we know the big reveal, after all, that the stranger on the road is the resurrected Jesus. But maybe Cleopas needs this moment of unrecognition for his preconceptions and prejudices to be reconfigured.

And so, despite a long theological conversation, it’s only when the stranger breaks bread and gives thanks – a eucharistic moment that echoes the last supper – that the stranger’s identity is revealed. The Last Supper forms the basis of our communion services, speaking of Christ’s death, but this second meal is its bookend, the revelation of his resurrection.

Maybe we need to hold the revelation of Emmaus in our hearts every time we eat the bread and drink the wine, remembering not just the crucifixion but the fresh vision of Jesus granted us by his emergence from the tomb, the miracle we encounter when the Stranger on the Road turns out to be the risen Saviour.

That’s not a once-a-year moment of sacredness in the Spring. It’s every Lord’s Supper – no, it’s every day. Heaven knows I need to make resurrection a daily remembrance. As we walk with Cleopas into another week, may we meet Jesus once again, and find the Saviour in the Stranger on the Road.