This is the sermon I preached for Easter Sunday morning 2024…

So. We’ve sung songs of celebration. We’ve proclaimed that Christ is risen. Later, we’ll have the chance to decorate the cross with flowers to celebrate life bursting out of an instrument of death. But for a moment, let’s rewind slightly and look to Mary Magdalene. Because less than 48 hours ago, Mary witnessed Jesus being nailed to a cross. She watched as he was mocked and humiliated, she watched the person who had brought her hope and healing die the death of a criminal. And that must have been like a knife to her heart and her faith, seeing the person who she hoped would save the world being snuffed out as he was crucified.

Mary would have been familiar with crucifixions. The Romans used crucifixion to send a message and reserved it for traitors and rebels and slaves. It was a way of identifying a threat to Rome and ending it in the most brutal, humiliating and degrading way possible. Not long after Jesus was born, a rebellion broke out 4 miles down the road from Nazareth; the Romans marched in and crucified 2,000 people along the roadside, leaving them hanging in shame and disgust and defeat as a horrible reminded of what happens to you if you mess with the power of the empire. Smaller scale crucifixions like Jesus? Dump them in a mass grave and forget about them. Crucifixion wasn’t just about execution, it was about scrubbing your name from history.

Jesus avoided that fate. A secret follower of his, Joseph of Arimathea, allowed Jesus to be buried in a family tomb, allowing him to be laid to rest with at least some dignity and honour. That was Friday.

But now Sunday is here. Mary rises after the sabbath day’s rest, not even waiting for daybreak, and goes to that garden tomb to anoint Jesus, to do what she can to lay to rest her hopes and her saviour. The grief is still raw, a terrible grinding hurt in her heart, every step taking her closer and closer to confronting the reality that Jesus is dead, that Jesus is gone. All she can do now is mourn.

And then the latest horror – she gets to the tomb and it’s been opened, the massive stone that once blocked its entrance rolled away. Who did this? Graverobbers? Hardly, it’s not like Jesus owned anything worth stealing. The Romans? The Temple authorities who had orchestrated Jesus’s lynching in the first place? Maybe. Maybe they wanted to obliterate Jesus’s memory even in death.

Mary runs to tell the disciples, Peter and John running to the tomb to see what’s going on. John outruns Peter, because hey, this is John’s gospel, but on reaching the tomb Peter overtakes him, running straight inside. He sees the grave clothes but no body. The men graciously accept that Mary had been telling the truth and then they…

Well, they go home. And Mary is left, standing in the garden, heartbroken and alone.

Don’t let that pass you by. Mary is standing in a garden.

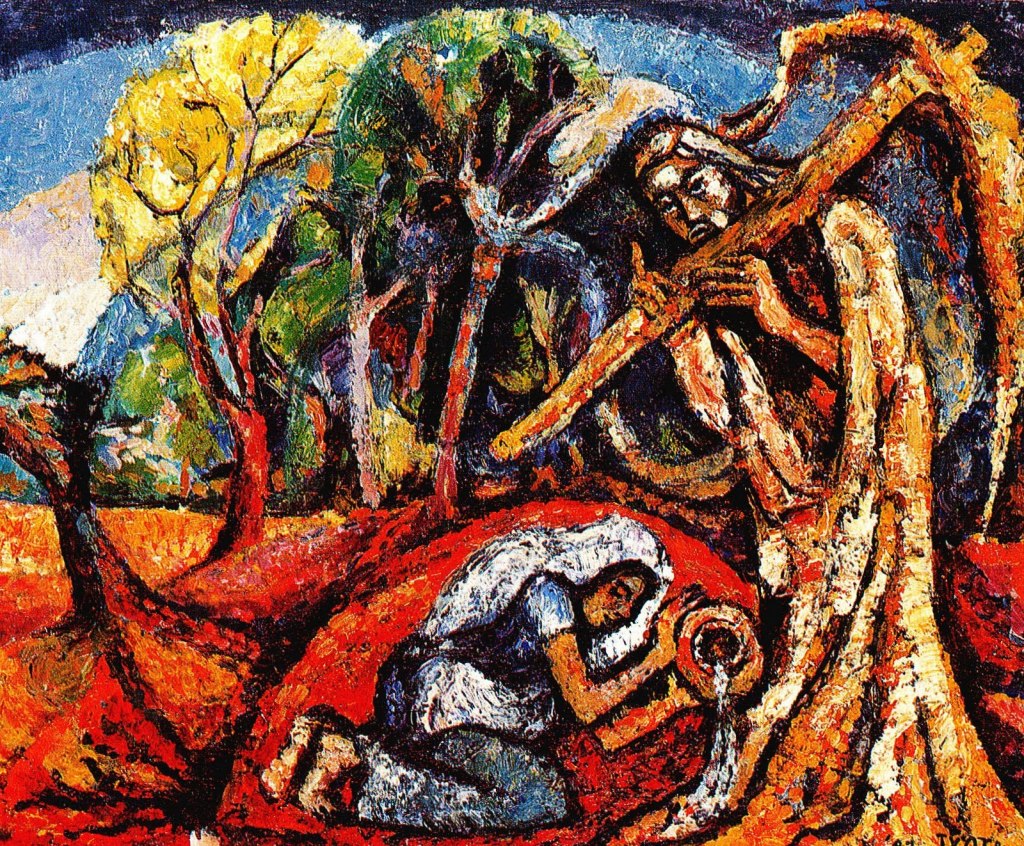

A long, long time ago, God planted another garden on a holy mountain. Here he places the first man and the first woman, Adam and Eve created to be co-regents of creation. They tend the garden and walk with God, and it’s a place of perfection and communion with the Lord himself. Eden is what creation is meant to be, but sin and death and Hell invade it, they tempt Adam and Eve and bring about the fall of humanity, and the garden is lost to us. And as God closes off Eden, he curses the serpent who instigated all this in the first place; although the serpent will continue to strike at humanity, a descendent of Eve will ultimately crush the serpent in turn. With a lot of hindsight, this is the first hint of Easter, given as humanity is ushered into an uncertain future.

But as they move into that future, God is with them and he promises to continue to be with us. Fast forward to Revelation, a strange book full of monsters and bizarre images that ends with a beautiful picture of the City of God. The author of Revelation writes that:

The angel showed me the river of the water of life, as clear as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb down the middle of the great street of the city. On each side of the river stood the tree of life, bearing twelve crops of fruit, yielding its fruit every month. And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. No longer will there be any curse.

The City of God, in which all curses are broken and death is no more and which in the people of God will once more walk beside him, is full of trees and fruit and healing and life. The City of God is a garden city.

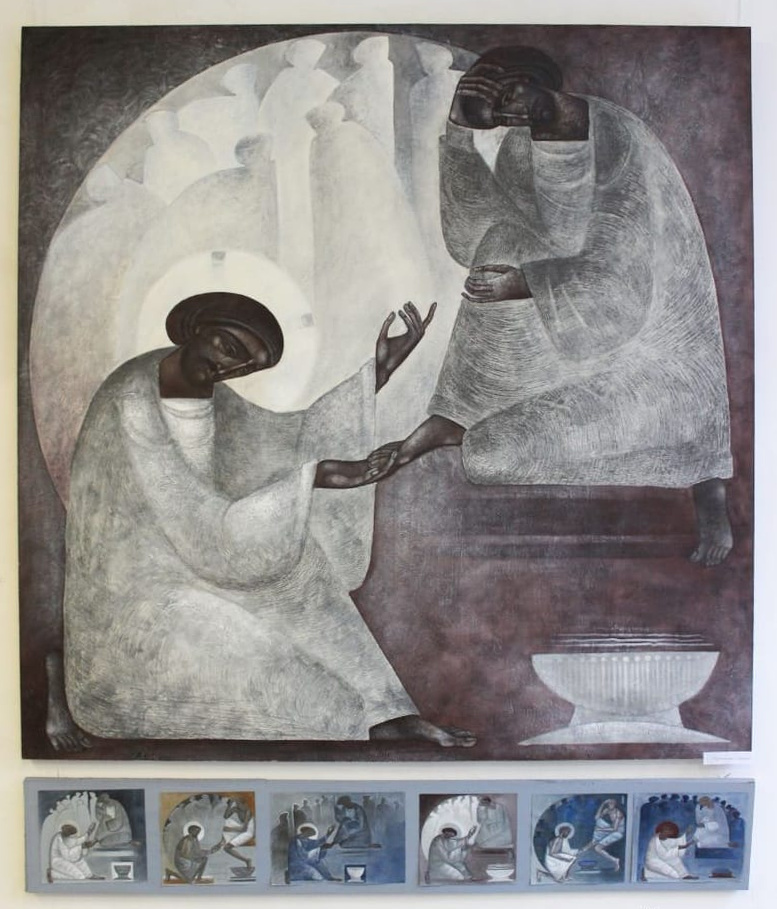

One garden at the creation of everything. Another garden at the re-creation of all things. Here in the middle, Mary stands weeping in a third garden. She dares to look into the tomb again, hoping that she and Peter and John were all mistaken. She looks into the tomb again, but now there’s someone there, two angels who ask her why she’s crying.

“They’ve taken away my Lord, I don’t know where they’ve taken him, I…I…I…”

Then another voice asks her the same question: “Why are you weeping?” She doesn’t recognise this person, she thinks he’s the gardener and she’s distracted by the tomb and the angels, looking back and forth and saying: “Please, sir, if you’ve moved him, just tell me where he is, I want to deal with all the arrangements, if you need me to move the body I’ll get it sorted, I…”

And then the gardener says one word. He says “Mary.”

He says “Mary” and the penny drops, suddenly she recognises who she’s talking to: “Rabbi!” Teacher. Jesus himself.

It’s the most profound mistake in the Bible. Jesus wasn’t the bloke paid to mow the grass and pick up the litter in this particular garden, but in the moment, Mary isn’t wrong, she’s a prophet. Because God has always been a gardener. Eden and the prophesied City of God are evidence of that and through the death and resurrection of Jesus, access to those sacred gardens is restored. And so is hope and life and forgiveness.

It’s impossible to discuss Easter without talking about new life. Sometimes that’s the sudden, miraculous revival of what once was dead, but often it’s a slower resurrection, a cultivation carried out by a loving and patient Gardener. Sometimes resurrection takes longer than three days – the death of hope or love isn’t always reversed overnight. But new life is coming. Mary’s grief turns to joy, she goes from survival to revival.

There’s a moment at the end of The Lord of the Rings when the lead character, Frodo, wakes up. The last thing he knew, he’d been wounded and traumatised by everything that had happened throughout the book, and as he closes his eyes he thinks it’s for the last time. But no, he wakes up and then he’s then reunited with a friend he thought was long dead. And he’s so overtaken by joy that he blurts out “Is everything sad going to come untrue? What’s happened to the world?!”

We live in a world where the sad things are very real and they feel very true. But here on Easter morning we celebrate the deeper, eternal Truth that lies behind this world. And that can be difficult to grasp, because sometimes the garden of this world feels more like a wasteland. But at the core of everything is this resurrection moment that allows all things to be reborn. Maybe not immediately; maybe the garden is just soil full of seeds at the moment, maybe new life slumbers beneath the surface for a winter. But the garden isn’t a wilderness anymore. Hope can be reborn, faith, peace, love.

I have a bit of an imaginational heresy, that one day in Heaven, Mary tracks down Eve, gives her a hug and says, “I was in a garden too, it worked out okay.” Because she met the true Gardener. He’s the new Adam who got it right; the one who reopened the gates of Eden and shows us the way inside. Walking through the trees of the Garden, we’re called to tend the world, to bring tool belts to broken places, to bring first aid kits to broken lives, to bring tears, coffees and casseroles to those who mourn, to bring wine and cake to those who celebrate. Easter isn’t just a yearly festival of chocolate and bank holidays, it’s a way of life.

And so we celebrate, because Christ is risen. In one of the set readings for today, the Old Testament prophet Isaiah had a vision of God throwing a great banquet for all peoples. He imagines God himself preparing the meal, breaking out the finest wines, the ruler of the universe serving as chef and sommelier because he’s celebrating the defeat and destruction of death itself. And with that, God will wipe away the tears from all faces and take away his people’s disgrace from all the earth. This is the great heavenly banquet, the ultimate party, the restoration of all that is broken, the forgiveness of sins. And the guests at the party respond to all that God has done saying “This is our God; we trusted in him, and he saved us. This is the Lord, we trusted in him; let us rejoice and be glad in his salvation.”

Isaiah sees all this taking place on a mountain. A very specific mountain, in fact, Mount Zion in Jerusalem. The city where Jesus died. The garden where Jesus rose. Soon we’ll have the opportunity to anticipate that final celebration once more and put flowers around the cross. And even if you don’t have flowers, please go and spend a moment out there. Because at the foot of the cross we can remember the things we’ve done wrong, the sins that haunt us, the regrets and the loss and the heartbreak and the guilt, we can remember all these things and lay them down. Because the cross is empty. The cross is empty and Christ is risen, and the power of sin and death and hell no longer have to hold us, they no longer need to drag us down, they no longer have the power they once did, because two thousand years ago, Christ was nailed to a cross and all those powers thought they’d won. But days later, in that garden, Christ rose again, he took their power and broke it in two and now we can be free. Now we can be restored. Now we can be born again.